NEWS

June 6, 2023

IN BRIEF

#PowerUp is a series of articles honing in on how South Africa’s electricity supply crisis is affecting young people. Written by Jaco Roets and Sara Hoenes Like many young students preparing for exams, Funeka Mpofu spends odd hours studying. However, for Funeka, his inconsistent hours are not by choice. Sweeping power cuts across South Africa are the worst they’ve been in more than two years. The blackouts (locally referred to as load shedding) are hindering the ability of young people to study and apply for jobs. For Funeka, this meant low scores on his college entrance exams, and another year [...]

SHARE

#PowerUp is a series of articles honing in on how South Africa’s electricity supply crisis is affecting young people.

Written by Jaco Roets and Sara Hoenes

Like many young students preparing for exams, Funeka Mpofu spends odd hours studying. However, for Funeka, his inconsistent hours are not by choice. Sweeping power cuts across South Africa are the worst they’ve been in more than two years. The blackouts (locally referred to as load shedding) are hindering the ability of young people to study and apply for jobs. For Funeka, this meant low scores on his college entrance exams, and another year of studying and trying to find work, delaying his dreams of studying math, science, and psychology at university.

South Africans have endured load shedding for more than ten years, but 2022 was the worst on record with 207 days of rolling blackouts, as aging coal-fired power plants broke down and state-owned power utility, Eskom, struggled to find the money to buy diesel for emergency generators.

Those that can afford extra internet data, generators, and solar panels are managing to cope, but for many, their studies, businesses, and ability to work from home are on the line, widening the gap between the digital haves and have-nots. With limited access to online education and work options, citizens who are already struggling to afford the cost of living find themselves further behind.

Perspectives From the Ground

Accountability Lab conducted informal interviews with artists, students, and small business owners at Makers Valley in Johannesburg to better understand how the electricity crisis was affecting them.

Tumi Moroeng is the Founder and Managing Director of Makers Valley. When load shedding started over ten years ago, he didn’t pay much attention. But now, his entire life – even his sleep schedule – is affected by the power cuts.

“I don’t sleep properly. I might rush in the morning to get here before 8am so I can work before the power cuts out at 10am – and then sometimes the power cuts out before 10am.”

When it comes to his business, Tumi says he’s not able to get as much done and the power cuts often leave a large backlog of work. “In a month, I usually write three or four proposals. With load shedding, it has been about half of that,” he said. “Or perhaps I have a big report. Because I don’t have the latest software, I don’t have backup. When the power goes out, I have to start all over again,” Tumi added.

Tumi also shared that Makers Valley has lost out on funding opportunities because he’s not able to be online during load shedding to answer a donor’s questions or get a requested document in on time. His artists may miss out on jobs because they can’t attend Zoom meetings. All of this means fewer resources for the artists and changemakers at Makers Valley. “Digitally speaking, we cannot sustain ourselves.”

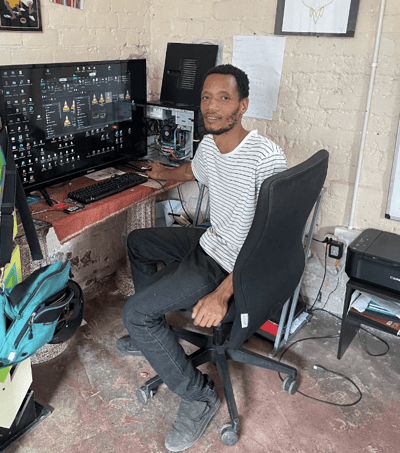

Lerato Molofe is a digital artist and illustrator who works on 3D modeling in Maker’s Valley. Because his work involves using computer programs and the internet, he is also unable to work during load shedding. Inconsistent hours have also cost him hours of work.

“Let’s say you’re working on a 3D model and you’ve already figured things out, he shared. “Now you’re just flowing. Sometimes you forget to save. It happens. Maybe you forget the schedule because you are invested in your work. All of a sudden, the power goes – boom! And you find that two/three hours of progress just disappears.”

Improper shutdowns are wreaking havoc on his computer and Lerato will soon have to pay for repairs or a replacement computer – costs aren’t in his budget. “I know it’s going to be extra costs that I didn’t intend for, but you just have to adapt. This is our reality.”

These challenges are not isolated incidents – local economists estimate that power cuts are costing the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) 4 billion rand ($232 million) per day.

Community Impacts and Mental Health

Beyond the collective economic costs, South Africans are individually feeling the emotional and economic burdens of load shedding. Throughout Johannesburg, tensions are high among and between citizens and people are looking for someone to blame. We asked how the community at Makers Valley was coping with the stress of unreliable electricity.

“People feel defeated,” said Lerato. “[They feel] like there’s nothing they can do. They just wait it out. When [the electricity] comes back on, they quickly go back to what they were doing with the time that they do have.”

“There’s an energy of depression,” Tumi shared. “Power cuts, pollution, unemployment – social anxiety is the result. There’s a collective burnout and depression.”

Power cuts are deepening socio-economic divides as people in low-income communities are also having a hard time keeping their electronics functioning well when the power suddenly shuts off. Throughout their communities, Lerato, Tumi, and Funeka hear about refrigerators, microwaves, and radios all breaking or blowing out, and families don’t have the funds to replace them.

Food waste is another issue. “We’ve got a fridge at home – the food is rotting. What do we do with that?” asked Tumi. “You have a family that buys chicken that week, and now the chicken goes bad and they have nothing to eat,” he added.

Young student, Funeka, has seen the effects of load shedding manifest in safety concerns for his community. “As soon as the electricity cuts off in the evening, it raises crime rates. People are getting mugged when they are walking home from work. It’s not safe in some communities. Some shops are forced to close early because of robberies,” he said.

We asked what might happen if load shedding continues, the collective worry was palpable.

“I can see this playing out and losing out on more opportunities and more work,” Tumi said. “I do understand the impact fossil fuels have on the environment, however, I cannot afford solar panels,” he added. “I’m part of a generation that can’t afford alternative energy. We don’t even understand how nuclear works. We’re told the only way to change it is to raise taxes – and we can’t afford that.”

“What will my future look like if load shedding continues?” said Funeka. “I can’t really imagine. All I can think of is that my life will be becoming worse and worse, day by day.”

Not All Hope is Lost

While the energy crisis has undoubtedly caused a myriad of issues for South Africans, a culture of resilience is unmistakable among the people we met. Creatives like Tumi, Lerato, and Funkea are uniquely positioned within their communities to bring people together, share information, and develop solutions together.

“How about when there are power cuts, we encourage the community to participate in guided tours [at Makers Valley],” said Tumi. “Let’s explore the community. Maybe this is a way to get conversations started.”

“Most South Africans don’t know and understand how to use electricity efficiently,” Tumi added. “Because when Eskom came about, they didn’t onboard the community. What they said was you get free electricity, education, and communication. I was told that this system was built for my benefit. I trusted the system and now it has failed. Perhaps if our community could understand electricity, it would be easier for people to understand how to save it. Then, maybe we can gradually start to talk about, practically, moving from the system to something more just.”

Despite the challenges, Funeka still believes in the power of South African youth. “When thinking deeply about it, while the government is in charge, South Africa’s future is dependent on the youth,” he said. “Of the people that can help in mitigating the problem, the youth could play a really big role in the sense that all the programs that we’re participating in are innovative and creative. The truth of the matter is that our government is full of old people. They have to step down for the youth.”

When thinking about solutions, Lerato adds, “I think maybe we need to change our minds and take action to make things better in the future.”

“I haven’t seen this new ‘Just Energy Transition Plan’ that the government has created, but I guarantee you that the community – innovators and makers – are not in it,” Tumi said. “For me, another immediate solution would be – before any money is spent, before anyone is commissioned to do anything – can we literally start engaging and consulting the community all across the board?” he asked.

“Everyone needs to be invited and asked how they understand the current problem and how they can do something to fix it,” said Tumi.