NEWS

October 21, 2020

IN BRIEF

eedev

SHARE

ONE and Accountability Lab recently convened a panel discussion to reflect on structural inequities in the development sector. Designed as a safe space for partners and colleagues to delve into the ways that the sector contributes to racial inequality, the webinar unearthed some hard truths around how international development organizations may begin to right some of the sector’s wrongs.

What could racial equity look like in international development? This is the question the webinar posed, along with an invitation to participants to move the global conversation around racism and inequality forward through tangible action items for the sector.

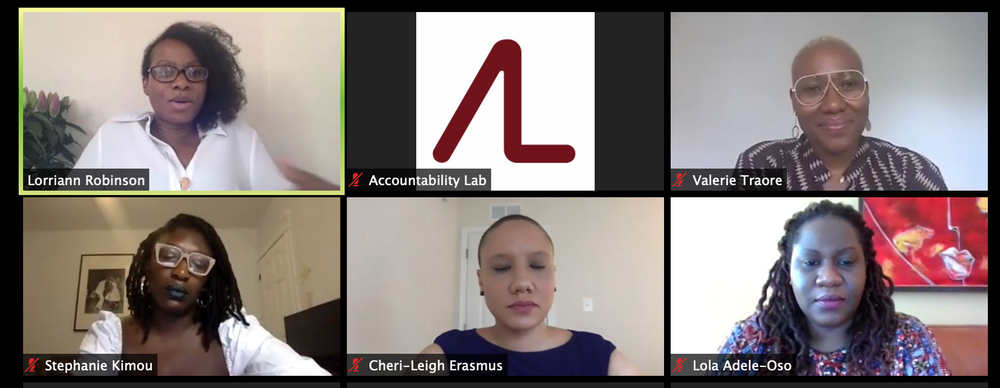

The discussion was moderated by Global Director of Learning at AL, Cheri-Leigh Erasmus, who opened it as a welcoming space, free of judgment, to tackle inequality at a systemic and behavioral level. The expert panel comprised activist voices from around the globe. It included Lola Adele-Oso, Founder and Chief Executive of LOS Lifestyle Co.; Lorriann Robinson, Founder and Director of The Advocacy Team; Stephanie Kimou, Principal Consultant at Popworks Africa; and Valerie Traore, Executive Director of Niyel.

Adele-Oso kicked the discussion off with a focus on the gap that existed in the international development sector for fearless organizations willing to “push the limits without fear of impunity”.

“The fundamental premise of international development is flawed. It’s based on an anti-blackness but also it is based on a power dynamic that always keeps those who are considered beneficiaries, on the receiving end, without equity or without a real voice,” she said.

Singling out indigenous NGOs, particularly in Africa, Adele-Oso added that they were often the ones doing the work in-country but generally not included in the creation of prescriptive solutions that were brought into their communities.

“When you take a look at how funding flows, it often does not match the work that is needed on the ground,” she said.

A study she was part of involving more than 100 NGOs in Nigeria, Uganda and Kenya revealed that most of them had similar complaints about the sector. These related firstly to the absence of systems for knowledge transfer. Many development organizations neglected to implement processes that ensured a solid way of transferring knowledge in order for indigenous institutions to continue the work.

Additionally, many organizations were accountable to their funders, rather than the communities they were operating in. “A lot of funders are looking for prescribed ways of addressing issues without having the people who – quote unquote – have these issues, at the heart of these consultations.” The sector needed to acknowledge that international development work was not a linear process and that metrics for impact didn’t necessarily work across borders.

“It’s messy and not a lot of funders are up for that complication – and for allowing solutions to be generated from communities and wholly-owned by communities.

The case for accountability

Adele-Oso added that many funders could be rightfully accused of supporting organizations that often had no background in the subject matter. These organizations managed to raise a lot of money without any checks and balances for holding them accountable for this funding. She also criticised international organizations that deploy primarily white country teams and hire indigenous people for sub-administration or implementation simply to ensure community buy-in.

“The movement for reclaiming our space is here and if organizations don’t figure out their role and how to embrace the changes that need to happen, then they’re going to find themselves in a situation where possibly a lot of people are going to keep calling for them to be out of their countries. They may face other hard policies or taxes that will be levied against them by governments and other entities.”

On a campaign level, Robinson urged INGOs to implement targeted efforts to ensure that more black people and minority voices were represented in the leadership of advocacy and campaigning efforts. “Very practically, this means that organizations need to be deliberate about recruiting more black people into advocacy director, campaigns director, and policy director roles. These mono ethnic leadership teams and coalitions just cannot continue in my view,” she added.

Further than that, Robinson encouraged organizations to be bolder in challenging existing power imbalances in the multilateral system and the make-up of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) specifically.

“We have a situation whereby the leaders of the largest aid spending countries get together and decide the rules about what does and what doesn’t count as aid. What that means consequently is that there are types of spending that are permissible within the rules that very few of us would recognise as within our understanding of aid. NGOs are generally focused in my experience on challenging the rules rather than the system and make-up of those organizations,” she commented. There was a gaping opportunity for countries from the global south to be represented on the DAC.

Countering anti-black racism

Kimou took up this mantle of structural reform, pinning the decolonisation of international development as an essential framework to challenge anti-black racism at an institutional level. She positioned international development as a product of colonization and white supremacy culture, and urged deeper interrogation by INGOs of where and how colonial paradigms showed up in the sector.

Four things in particular needed attention, Kimou said. First, the acknowledgment of the trauma and inequality perpetuated by colonialism in Africa was critical. Second, the inequities in pay scales for people not living in North America and Europe needed to end. Third, she highlighted the scourge of poverty porn that continued to instrumentalize the trauma of black and brown people for the benefit of fundraising, and finally, Kimou drew attention to the broad need to better honor locally-rooted expertise. “This means not using their experience for campaigns or utilizing their language skills, but because we really read their work, are inspired by their art, cite their research, and see them as experts and not a means to an end,” she said.

“For me, to decolonize international development is an act of love – and this concept I borrowed from Dr Rosales Meza, a Mexicana psychologist who believes that if you’re working in a white patriarchal system, rooted in the colonization of black and brown people, it is a radical act of love to make space for the deconstruction of those paradigms.

“I urge all of us to interrogate the windows of opportunity; understand colonial histories and trauma when you’re working as a development practitioner to dismantle racist development norms … and interrogate how the manifestations of white supremacy and racism are showing up in your institutional norms. It’s also about honoring local expertise and elevating it as a tool to decolonize international development.”

Traore took this point further, challenging the distinction between local and global. The panellists advocated powerfully for development practitioners to create more progressive language for the sector.

“Let’s stop calling it local; expertise is expertise. Because local makes it small, local makes international expertise wider, deeper, and better than local. … I think the question is what expertise are we looking for and then get the expertise that is closest to where we want to see the work done. Then it’s no longer about local versus global,” she said.

This approach would also prevent a situation where indigenous organizations and experts were effectively penalised by the semantic distinction, through fewer resources or lower payment rates. Aligned to this, Kimou put forward an alternative to talking about localization and aid, too. “I’m trying not to use the word ‘aid’ anymore and I’m talking about reparations, because these are the things that are owed to black and African people. … I don’t want to talk about localization anymore. I want to say relinquishing unearned power. International organizations had unearned power and unearned access,” she said.

Moving beyond the optics

The panellists had practical advice for organizations that were unsure of how to deepen their efforts to encourage greater racial equity – both internally and externally.

First, hire more black people into positions of leadership. “What we’ve seen is institutions who are doing things where the optics are there, such as giving people Juneteenth off in the United States, or recognising in Europe that poverty porn has been used in certain ways, or recognising that on the African continent how inequitable pay scales are something to address. But now we’re moving towards action.

“I don’t think any of these institutions that are inherently racist – and honestly anti-black in a lot of ways – will be able to move forward authentically without black people in positions of leadership,” Kimou said.

Adele-Oso reiterated that the role of funding, along with donor expectations, could also not be discounted. Organizations needed to be willing to have honest conversations with funders about how they may not meet metrics set at the outset of programs, or may not reach the agreed milestones in one funding cycle, without fear that they would be penalized or defunded as a result.

“It goes back to this concept of the black and brown bodies generating money for you. If you bring it down to basics, it’s about money. A group of people are building, growing and implementing off the bodies of black and brown people. So we have to be able to challenge those funding sources and say, ‘This is not how this works’. And the donors have to be willing to say, ‘Ok, how can we adjust for the unknowns’.” Robinson added to this by praising those development organizations that were creating baselines and indicators that were aligned to their own vision and mission, rather than those of donors.

Related to this, Traore said that because funding decisions were decided at a board level, it was critical to ensure that organizations’ boards were diverse. “There are spaces where we’re still not admitting that the sector is racist. Admitting it helps you look at all of it with honesty and ask, ‘How do we fix it?’. It doesn’t mean every individual person is bad; it’s understanding that this is what the system is,” she explained.

“When boards are diverse, that work of just accepting where the world is starts at the board level and gives permission to the leadership, even the CEO as a black woman, to be able to run the organization with authenticity and not feel like she has to fight all the time with not only her board, but even people in her own leadership team,” Traore said.

Robinson said black women leaders in the sector were increasingly setting the bar impressively high and leading the way in calling for systemic and purposeful change.

“The things that encourage me more than anything are the often-black women who are setting up independent organizations to challenge the systems and structures; and those who are operating internally – perhaps at a level below the board or directorship – and increasingly feeling empowered to challenge their organizations and push them in a new direction.”

Actionable steps for development organizations to consider:

- Honor indigenous expertise.

- Implement secure and sustainable systems of knowledge transfer with partnering organizations.

- Ensure accountability mechanisms exist for the communities you work in and with, as much as they exist for your funders and supporters.

- Co-create your programs and plans. Allow solutions to be generated and owned by communities.

- Funders must ensure that grantees and sub-grantees work equitably and with accountability.

- When creating program metrics, consider that they may not work across borders, particularly in the Global South.

- Hire people equitably and fairly. Work to ensure that your international and in-country teams are diverse at senior and junior levels.

- In particular, ensure that campaigns and advocacy teams are multi-ethnic.

- Work to ensure your board is diverse.

- Lobby for greater diversity at multilateral organizations to help influence regulatory funding institutions.

- Interrogate where and how white supremacy culture may be showing up in your organization, whether through pay inequities, or using colonial and other unjust systems and behaviors.

- Consider the words you use and retire language that entrenches unearned power dynamics.