NEWS

August 11, 2015

IN BRIEF

By: Alison Campbell, Senior Director for Global Initiatives at Internews. This article was originally published by Internews. In Nepal, a band of local volunteers are trying — with SMS, radio, the Internet, and old fashioned door-to-door reporting. For survivors, the immediate priorities in a disaster such as an earthquake seem clear: Get to safety. Help your family and those around you. Reach the people you love and tell them, “I’m OK.” A Nepal radio reporter interviews earthquake survivors. Credit: Madhu Acharya/Internews But after the initial crisis is over, survivors are faced with a million uncertainties and questions as they try to piece together [...]

SHARE

By: Alison Campbell, Senior Director for Global Initiatives at Internews. This article was originally published by Internews.

In Nepal, a band of local volunteers are trying — with SMS, radio, the Internet, and old fashioned door-to-door reporting.

For survivors, the immediate priorities in a disaster such as an earthquake seem clear: Get to safety. Help your family and those around you. Reach the people you love and tell them, “I’m OK.”

But after the initial crisis is over, survivors are faced with a million uncertainties and questions as they try to piece together their shattered lives and communities.

In Nepal, where April’s earthquake left millions displaced from their homes, the road to recovery is long and littered with rumor and misinformation.

“I have heard that the government will issue us passports

and send us abroad for work.”

“The government said it would provide low-interest loans to rebuild houses, but it hasn’t started the process yet. We are confused.”

“People here think the earthquake victim ID cards are useless.”

“All of my neighbors have got Rs 15,000 each and built shelters weeks ago. When I went to the VDC office, they said the money in my name had already been taken.”

Each of these comments came from residents in ten of Nepal’s 14 districts most affected by the earthquake. They all point to a lack of trusted information, or confusion in processes that haven’t been properly communicated. This is typical of the aftermath of crisis situations.

When people have little reliable information available to them, rumors, myths and misunderstanding spread rapidly, adding greatly to the stress and anxiety of already traumatized people.

Volunteers, working with Accountability Lab, Internews, Local Interventions Group and other local partners have launched Open Mic Nepal, a systematic information loop that tracks, investigates, and reports back to local communities on damaging rumors.

The project is built on a combination of shoe-leather reporting and simple technology that allows broader analysis and dissemination of facts. The system was successfully piloted to fight Ebola rumors in Liberia.

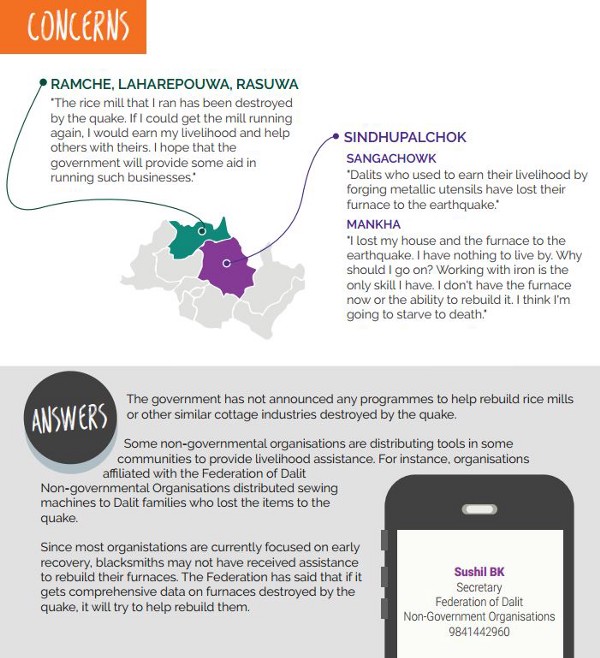

Here’s how it works. Volunteers from multiple organizations who are assisting earthquake victims to access aid and services collect and text in the rumors and concerns they hear from local populations as part of their daily routines. A recent OpenMic bulletin was based on conversations with 450 people in a one-week period. The OpenMic team then geolocates, analyzes, and reports on the most pressing or common concerns.

Volunteers from multiple organizations who are assisting earthquake victims to access aid and services collect and text in the rumors and concerns they hear from local populations as part of their daily routines. A recent OpenMic bulletin was based on conversations with 450 people in a one-week period. The OpenMic team then geolocates, analyzes, and reports on the most pressing or common concerns.

The bulletins are also shared with the on-the-street volunteers themselves, to complete the feedback loop, as well as with the wider humanitarian system.

By keeping the rumors intact in the bulletins, the OpenMic project allows local media and humanitarians not only to debunk the rumors, and address the factual misinformation, but also to investigate why certain rumors are so popular. Research shows that rumor mongering can serve a social “sense making function” — a kind of collective problem solving: the analysis of persistent rumors can be very revealing, many are not malevolent and do contain versions of truth. Tracking them provides information about information eco-systems, mistrust, and information gaps left open by government and humanitarians.

Building Trust

While radio is active throughout Nepal, and community radio stations have worked tirelessly to respond to the crisis, they don’t have the manpower to report on every local issue, or the birds-eye view to see what rumors are spreading.

But local media is a critical partner in closing the loop between official communications and the information needs of local communities. Radio stations can translate from Nepali to other local languages (Nepal has 122 mother tongues) and can contextualize stories for local audiences, with the trust they’ve built in communities — trust that official messages from the government or humanitarian agencies might not have.

Aid organizations are often disconnected from local media, and face an uphill battle in communicating with local communities.

“Humanitarians expect people to understand why they are there and what they do,” says Indu Nepal, Internews project director in Nepal. “But that is not the case. Locals see people, often foreigners, are here, and they seem to have means to help, but who are they helping? What are they doing exactly? How long will they be here? What can I expect? There really needed to be a system where the most trusted sources of information — local media — can also tap into these international sources of information, and make a connection back to the people.”

Open Mic Nepal is presented by Internews and #quakehelpdesk implemented by Accountability Lab and Local Interventions Group.