NEWS

January 2, 2024

IN BRIEF

Cities are made up of intricate systems with many interconnected elements such as transportation, housing, water, waste, politics, and health. The interaction of these elements can yield transformative outcomes, like establishing health centers fostering job opportunities and educational growth. Conversely, it can also introduce challenges, such as industrial activities adversely impacting the water supply. Despite the seemingly boundless complexities inherent in cities, sustainability is essential. Therefore, it is vital to cultivate accountable cities where decision-makers are aware of their impact and answerable to the citizens they affect. This accountability, rooted in transparency and responsiveness, becomes the linchpin for building trust [...]

SHARE

Cities are made up of intricate systems with many interconnected elements such as transportation, housing, water, waste, politics, and health. The interaction of these elements can yield transformative outcomes, like establishing health centers fostering job opportunities and educational growth. Conversely, it can also introduce challenges, such as industrial activities adversely impacting the water supply. Despite the seemingly boundless complexities inherent in cities, sustainability is essential. Therefore, it is vital to cultivate accountable cities where decision-makers are aware of their impact and answerable to the citizens they affect. This accountability, rooted in transparency and responsiveness, becomes the linchpin for building trust and generating the political will necessary to manage city systems, which also leads to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 – ushering in inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities.

What is a system of a system?

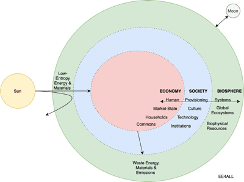

Cities as socio-ecological systems have three domains (social, ecological, and economic) that flow and interact (source). We can see the socio-ecological system in effect through the example of housing. Housing is a fundamental human right and happens to be at the intersection of several different systems. In the ecological domain, the house is a permanent environmental addition. It can either help (through urban farming programs, biodiversity in the garden) or hurt (pollution, energy consumption, and water consumption) its surrounding environment. For housing to function, it requires other systems, such as raw materials, water, and sewage. In the social domain, people living in a house depend on social norms. For example, if the housing is in an art-centric part of the city, it attracts more people who want to contribute to the art scene. Retirees might want something quieter and want to avoid living in such housing.

The housing can also reinforce discrimination through negative externalities in the market and policies such as redlining. In the economic domain, housing supply and demand depend on various systems, such as the job market and the value of the location. Other amenities like a nearby metro station, a grocery store, or parks can also affect the price of housing. A change in the ecological domain utilizes and affects the economic and social domain, and vice versa. For example, say a marginalized group can only find housing in one part of the city (social domain), and the housing has old and rusted infrastructure. Due to marginalization, city-focused investment in other parts can lead to less capital in the marginalized area (economic domain). This leads to the housing infrastructure worsening (ecological domain), where the plumbing breaks and leaks into the groundwater, causing a public safety crisis. On the other hand, fixing the housing infrastructure (ecological domain) could lead to a better quality of life for the marginalized community (social domain). The community can then spend more time and energy revitalizing the area (economic domain).

An all-encompassing view of sustainability

Sustainability is commonly only thought about as protecting the environment – or the ecological domain. However, when we make sustainability a goal for our cities, especially a goal that can lead to SDG 11, we have to think about sustainability in all aspects of the city: the social, economic, and ecological domains. This view of sustainability is referred to as the “Triple Bottom Line” in business (source), and we can adapt it to the city as well. In the social domain, a sustainable city strives for inclusivity, equity, and a high quality of life for all residents. This includes affordable housing, accessible healthcare, education, cultural diversity, and community engagement. Socially sustainable cities prioritize the well-being of their citizens.

Economically, a sustainable city has a goal to create a robust and resilient economy that provides a better standard of living for all. This involves promoting sustainable business practices, supporting local industries, and investing in green technologies. Economic sustainability also emphasizes long-term planning to avoid the depletion of resources and the negative impacts of short-sighted economic policies. The ecological domain sees a city strive to be carbon neutral, promoting biodiversity and creating developments that better the environment rather than harm it. As seen previously, aiming for sustainability in one area can also benefit other areas. An accessible farmers market, for example, can promote the ecological, social, and economic domains altogether (source). High coordination is needed for sustainable, triple-bottom-line development in cities – which is possible through accountability.

What can accountability do for a city?

For institutions to be deemed accountable, decision-makers must be answerable to the people they affect. These decision-makers should actively listen to and act upon the people’s concerns, increasing trust and overall political will regardless of ideology (source). A city is a complex socio-ecological system with various stakeholders (including employers, workers, parents, children, and even nature) influencing its functioning. The introduction of accountability fosters trust among these stakeholders, enabling smooth interactions and synchronization among all the systems.

Civic Action

We develop trust by transforming the city into an accountable institution, leading to sustainability. Accountability Lab’s pioneering Civic Action (commonly referred to as CivActs) programs demonstrate this. Accountability Lab’s Civic Action teams are crucial in bridging the gap between local communities and those in power. By electing Community Frontline Activists (CFAs), who act as volunteer journalists, communities can collect feedback through surveys and relay it to the relevant authorities. In return, the community receives validated information that helps facilitate conversations about critical local concerns.

The impact of CivActs can be seen in Nepal, where programs have been implemented in over 17 districts. Recognizing the benefit of CivActs, local government units in over eight municipalities have allocated a budget towards CivActs programs and have used data from CivActs to design programs that match skills with employment opportunities and other emergent outputs (source). The CivActs program has also been implemented in four districts across Zimbabwe. According to evaluations, 61 percent of citizens reported improved accountability and good governance. Additionally, 77 percent of participants noted that CivActs has allowed them to communicate their issues to those in power easily, a significant improvement from the baseline study where only 4 percent of citizens had such opportunities (source).

Integrity Icon

Integrity Icon is an initiative led by Accountability Lab to identify, celebrate, and support government officials who demonstrate exceptional accountability – instead of only focusing on wrongdoings. Integrity Icon ‘name-and-fame’ those who serve as positive examples of integrity in public service. The goal is to foster a cultural shift within institutions, promoting institutional integrity rather than individual integrity. This program shifts norms within the government so that the offices and bureaucrats that run them hold themselves to higher standards. It creates role models, which encourages young people with integrity to enter government and work on behalf of their communities instead of labeling the government sector as a ‘lost cause.’ Finally, it helps rebuild trust between people in power and citizens (source).

Conclusion

By adopting participatory approaches that involve a diverse coalition of stakeholders, cities can become sustainable socio-ecological systems. Accountability is crucial in the fight against climate change and is critical for achieving Sustainable Development Goal 11. Through a collective effort to prioritize accountability, we can work towards building cities that meet the needs of both current and future generations.