NEWS

August 22, 2023

IN BRIEF

Elections are an exciting and well-studied subject across the world. They attract a tremendous amount of this excitement stemming from their competitive nature and “peoples” enduring a belief in them as the best way to provide governors with legitimate province over governance, or the absence of alternatives. For some, elections are the essence of democracy and legitimacy, and a close approximation of the rule of the people by the people through evidence of their express consent to authority, itself a fundamental tenant of political legitimacy. Resultantly, elections invariably whip up a frenzy, as the public, commentariat, and scholars engage in [...]

SHARE

Elections are an exciting and well-studied subject across the world. They attract a tremendous amount of this excitement stemming from their competitive nature and “peoples” enduring a belief in them as the best way to provide governors with legitimate province over governance, or the absence of alternatives. For some, elections are the essence of democracy and legitimacy, and a close approximation of the rule of the people by the people through evidence of their express consent to authority, itself a fundamental tenant of political legitimacy. Resultantly, elections invariably whip up a frenzy, as the public, commentariat, and scholars engage in the often-futile processes of trying to pick winners and losers before ballot boxes are open and then explaining victories and loss post ballot counting.

Zimbabwe’s political commentary is replete with how its elections are shams, ritualistic because the ruling party, ZANU-PF, has mastered the art of electoral subterfuge, manipulating electoral systems, and turning elections into rituals that deceive people into believing that they have power in elections without choice. Through this deceit, as the late Professor John Makumbe argued in 2006, elections are conducted like clockwork and the incumbent emerge victorious, often thwarting the people’s choice, and desperately holding on to political power. This is probably true, and enough has been written to evidence this. However, the elections happen, the opposition participates and believes it can win. If we take this into confidence, the next question becomes how? How can the opposition win, if indeed elections are competitive, where are they competitive and where do the political gladiators have to win to secure ultimate victory?

In this article, I outline the competitive nature of Zimbabwe’s 2023 elections using a constituency categorisation system and data that I gathered for my PhD Thesis, Campaigning, Coercion, and Clientelism: ZANU-PF’s strategies in Zimbabwe’s presidential elections, 2008-13 which I augment with data from other research projects and my analysis to present a more complex picture on electoral competition in Zimbabwe. I start by briefly outlining the inherent unfairness of Zimbabwe’s pre-0dorminant First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) electoral system and its limited capacity to reflect the actual political landscape of the country. Utilising the concept of battlegrounds, I underscore the heightened competitiveness of the 23 August 2023 election and identify constituencies of particular significance upon which the election outcome may hinge. I end by offering insights into the pronounced focus on specific Harare constituencies by ZANU-PF and the CCC’s concerted efforts to secure rural support, given that both efforts are in constituencies where both parties are supposedly weak.

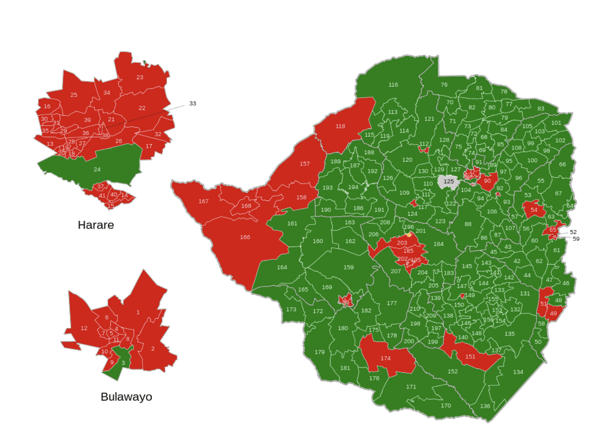

It’s the Electoral system, stupid

In the 2018 elections, ZANU-PF secured a dominant victory by claiming 145 out of the 210 available seats, translating to 68% of the total. The MDC Alliance, on the other hand, managed to secure 63 seats, representing 30%. Independent MP Themba Mliswa won the remaining two seats from Norton and the controversial Midlands politician Masango “Blackman” Matambanadzo, who represented the National Patriotic Front (NPF) got the remaining two seats. When visually presented on maps like Figure 1, it appeared that ZANU-PF had a sweeping influence across the nation (indicated in green), with sporadic pockets of support for the MDC Alliance (depicted in red). However, when we consider the popular vote at the parliamentary level and treat the country as a single constituency using presidential election results, the picture that emerges is more dynamic and becomes more complex regarding Zimbabwe’s partisan alignment dependent on actual margins of victory.

Figure 1: Zimbabwe’s Election Map from 2018 HoA Results

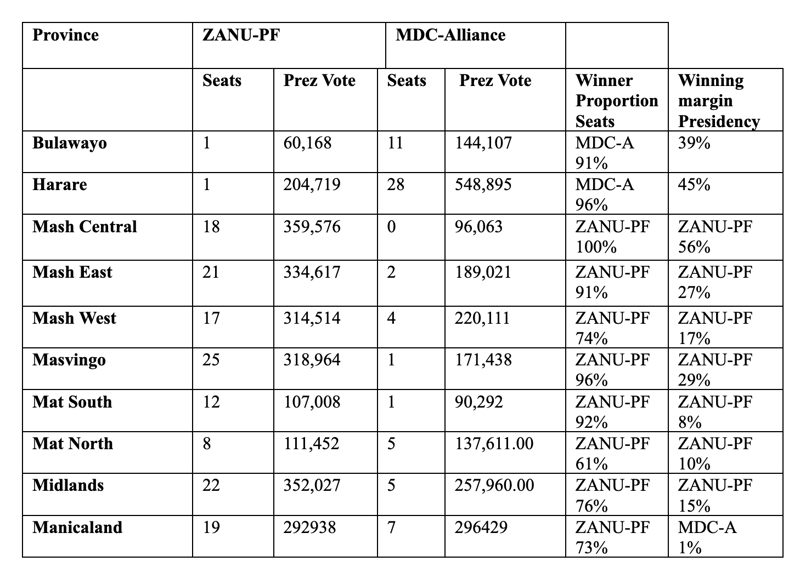

Zimbabwe’s predominantly First-Past-The-Post Electoral system, whose outcomes are depicted in Figure 1, produces a disconnect between actual support that political parties have, and the number of parliamentary seats that they accrue. This Winner-Takes-All system used to elect Zimbabwe’s lower house and local governments is distortionary and has led to unjust electoral outcomes that undermine the essence representation. For instance, in Matabeleland South province, despite a contest in 2018 between the ruling party and its main opponent, then, the MDC-Alliance, leading to a total vote difference of approximately 17,000 votes, ZANU-PF managed to secure all but one of the province’s 13 seats. Similarly, in Harare, where ZANU-PF garnered close to 30% of the vote, it accrued one seat. Even more perplexing is the situation in Manicaland, where the opposition secured the popular vote by a 1% winning margin, yet, ZANU-PF secured a staggering 73% of the seats as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Provincial Level Seats And Vote Share, Incumbent Versus Main Opposition

The outcomes shown in Table 1 show the inherent injustice and falsity of representation outcomes that emerge from the winner-takes-all electoral process. It highlights the incongruity between the popular vote and seat distribution and how the current electoral system does not adequately reflect the parties competitive presence in different geographic regions. Perhaps more importantly, the latter undermines the legitimacy of parliament as a house of representatives, as the representatives themselves do not fairly represent the national constituency and ignores the various significant cleavages and levels of political support across the political and geographic spectrum. This diminishes the extent to which elections can be accepted as a legitimate, institutionalised attempt to actualise the essence of democracy, translating the rule by the people into workable executive and legislative power ala Lindbergh.

A better representation of partisan alignment in the country comes from other elements of Zimbabwe’s mixed electoral system, where 60 female members of the HoA, 60 Senators, 10 Youths, and +/-590 women (30% of local authority seats) are elected through a party-list proportional representation system. Civil society and election watchdogs have suggested that this system be adopted across the board to ensure better representation and more cooperative governance in Zimbabwe, but to no avail.

Beyond the question of unfair representation outcomes, analysis that is based on the First Past the Post System leads to overgeneralisations and does little to direct campaigners toward where they should place their efforts and where they may be wasting their time. It also gives political enthusiasts limited to no information about the intensity of competition at the subnational level and why parties may be targeting constituencies that they do. In the pages that follow, I use presidential election returns data from 2018 and previous elections to map battleground constituencies and the possible zones of intense electoral competition as well as safe seats for the two main contenders in the 2023 election, the Citizens Coalition for Change, and the ZANU-PF.

Battlegrounds, Swings, And Lost Causes in the 2023 Elections

“Battleground,” as a characterization of constituencies, is seldom used in African politics and Zimbabwean elections. The preference is often for the term swing constituencies, but even this is scarce. One of the few studies that attempt to address swing constituencies in Zimbabwe is a Freedom House study from 2011 which defines a swing “as a constituency where the difference in vote tallies between the MDC-T and ZANU PF was 10% or less.” This aligns with generally accepted definitions of swing constituencies, equated to Battleground constituencies in jurisdictions like the UK. In the United States of America (USA), “battleground” states are the same as “swing” states, in line with the Freedom House (2011) definition. However, in the USA, the terminology denotes states that have regularly seen close contests between parties in previous elections and could reasonably be won by any leading contenders. Additionally, these states are considered critical to the overall outcome of the election.

While there is no formally accepted definition of Battleground constituencies, pegging the threshold at 10% does not reliably capture the entire universe of constituencies whose outcomes in elections can be “too close to call” in the Zimbabwean context. I, therefore, move away from the preceding conception to define battleground constituencies as constituencies in which the winner’s margin of victory is less than 20%, which given the volatility of elections in Zimbabwe, I consider too narrow for any candidate or political party to claim the constituency as a stroll in the park before an election. The MDC-T to ZANU-PF swings of the 2013 elections are illustrative in this respect, where Mugabe “recovered” from a 43% vote share in 2008 to mast over 60% in 2013, gaining a two-thirds victory in parliament from an almost 50-50 seat split with the opposition.

Battleground constituencies generally possess the common characteristic of not being discernibly dominated by one party or candidate regarding electoral outcomes. Different political parties and interests can battle it out electorally in battleground constituencies, knowing that they stand a 50-50 chance of winning and that a significant portion of constituents will give them the time of day and listen to their appeals. For instance, constituencies in the districts of Tsholotsho and Goromonzi have been battleground constituencies over time. The two Tsholotsho constituencies have alternated between ZANU-PF, Independent, and MDC T and Alliance, appearing to consolidate in the opposition’s favor and then swinging to ZANU-PF again. Gwanda South has been a consistent battleground with less than 15% winning margins but has yet to turn from ZANU-PF to the opposition since the 2002 presidential elections.

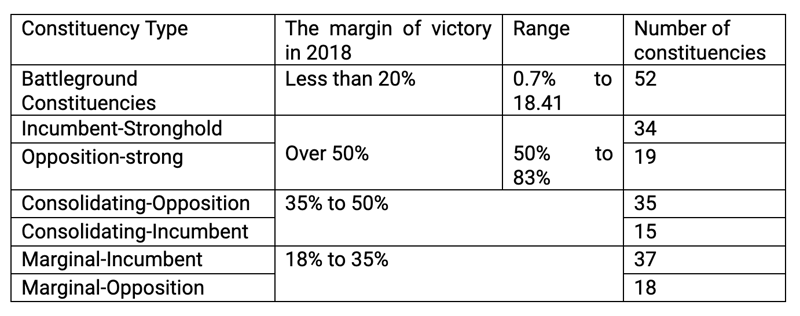

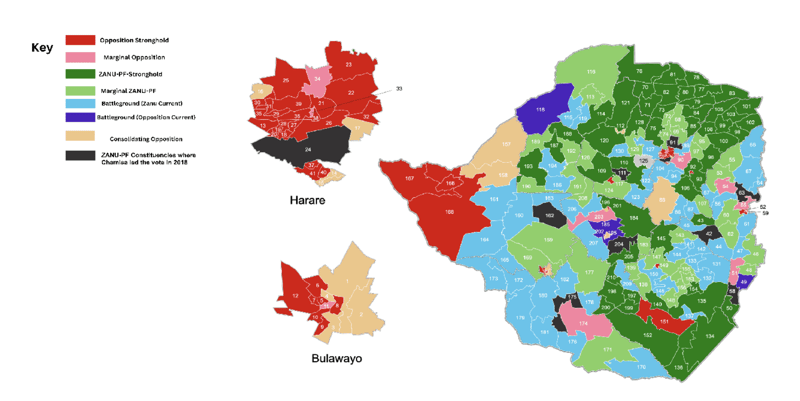

Figure 3, which is based on 2018 presidential election results underscores the heightened competitiveness of the 23 August 2023 election. It delineates a landscape where at least 52 constituencies are battlegrounds. Within this framework, Figure 3 illustrates several categories: firstly, there are the opposition’s lost causes, representing ZANU-PF strongholds (34 constituencies); secondly, there are ZANU-PF’s lost causes, signifying opposition strongholds (19 constituencies); and finally, there are the 52 battleground constituencies, depicted in purple for the CCC, sky blue for ZANU-PF, and black where Chamisa led the vote but ZANU-PF secured the seat. For a detailed breakdown of these numbers, please refer to Table 2.

Table 2: Constituency Types Ahead of 23 August elections based on 2018 presidential election results.

Figure 2: 2023 Electoral map based on seven categories ahead of election day

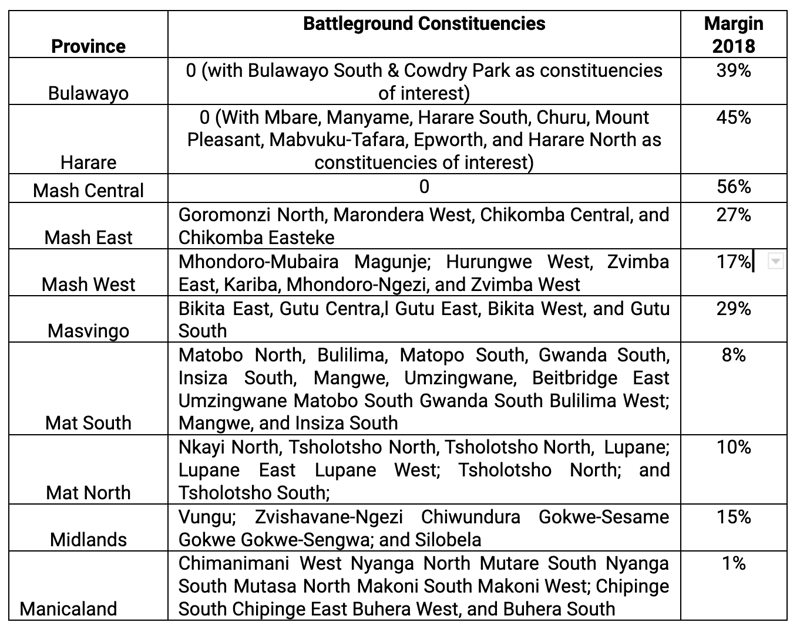

Table 3 contains the complete list of battleground constituencies based on the winning margins formulas from Table 2 and shows that the bulk of these constituencies is in the provinces with the lowest winning margins, as shown in Table 1. Mash West, Masvingo, Mat South, Mat North, Manicaland, and Midlands. Mashonaland East and the Midlands lean ZANU-PF, but the margins can be overcome. At the same time, Harare, Bulawayo, and Mashonaland Central are fairly decided depending on how far the dominant political parties can turn out their voters on election day.

Table 3: Battleground Constituencies across Provinces

Confounding Moves on the Campaign Trail

If the above is correct, one can be forgiven for asking why Chamisa and CCC wanted to launch their campaign in Mashonaland Central and why ZANU-PF seems intent on winning seats in Harare (Mabvuku-Tafara, Harare South, Mbare, Mount Pleasant, and Churu for example) or in Bulawayo ( Cowdry Park and Bulawayo South for instance).

For the CCC, the strategy for the 2023 election was a Chasing Strategy where the party sought new voters and supporters, especially in rural Zimbabwe, on the assumption that they have the cities and towns locked. This is likely why the Mugwazo (Rural mobilization strategy) was the centrepiece of CCC voter registration drives earlier in the year. A successful campaign launch in Bindura, Mashonaland Central, would have shown that the opposition can command attention and support in the strongest of ZANU-PF strongholds. The message would be if they can do that, imagine what they can do in shaky ZANU-PF constituencies.

In Mashonaland Central, a historical pattern has emerged where ZANU PF has consistently had a prominent political figure, akin to a “godfather” or “godmother,” exerting influence through key positions in the Presidium and Commissariat. Notable individuals who have played this role in the past include figures such as Mujuru, Kasukuwere, and Gezi.. There is no such patriarch or matriarch at the moment, and without a patriarch or matriarch, the opposition may be forgiven for thinking that the province is up for grabs. This situation was made even more likely by stopping Kasukuwere from being on the ballot. Bindura itself, being a town, was a good choice because it has trended from a battleground constituency, even having an opposition MP for Bindura South in 2008, to being a marginal ZANU-PF constituency in 2018. However, despite best efforts, Mashonaland Central is unlikely to turn opposition in the 2023 election because of the huge margins CCC would have to overcome.

Ruling party chasing urban areas

A short look at Bulawayo South and Cowdry Park

On the other hand, ZANU-PF has conducted an onslaught on some perceived opposition strongholds in Harare and Bulawayo. Part of what explains this is that although both cities are bastions of opposition support, the data shows that they are not impregnable. ZANU-PF has succeeded in previous elections to take Mbare, Harare South, and Bulawayo South constituencies. For the latter, the incumbent ZANU-PF MP, Deputy Minister Modi Rajeshkumar Indukant, legitimately fancies his chances and has the advantage of performance. However, part of his victory in 2018 was due to double candidates from the MDC-Alliance (Kunashe Muchemwa and Francis Mubvirimi). The candidates’ votes combined of 6,404 would have outpolled Modi, who got 5752 votes, while Chamisa outperformed all other candidates with 9853 votes to Mnangagwa’s 3939 votes.

For Cowdry Park, new dynamics come with new boundaries and heavy financial and infrastructural investments during the campaign. However, when placed on the old pelandaba-mpopoma boundaries, there is evidence of apparent interest in the constituency from ZANU-Pf, whose presidium visited it thrice in 2018 and staged its 2023 Bulawayo rally in the constituency. In 2018, Chamisa outpolled Mangangwa with 9504 votes to 4232. However, at the house level, the competition was stiffer, with the MDC-Alliance mastering only 7059 votes to its total opposition’s 7330, with ZANU-PF contributing 4079 of those votes and the rest from 15 smaller parties. The joint total of the other parties would have been enough to beat the MDC-A, which we proxy for CCC in the 2023 elections. In short, there is a chance that Finance Minister Professor Mthuli Ncube can fashion a winning coalition for the seat outside CCC supporters. He also has the advantage of credentials that some formerly CCC sympathisers can find attractive. At the same time, ordinary constituents may value the “development” he has brought and may bring as government Minister. His primary opponent, CCC’s Pashor Raphael Sibanda’s chances lie in a heavy Chamisa endorsement and possible presence, as well as his putting on his mobiliser trousers to ensure a solid turnout of the CCC’s base on election day.

However, both Bulawayo constituencies and others across the country are likely to be sites of ballot splitting with people voting across party lines on different ballots, i.e. a local councillor or MP and president who do not belong to the same party. they know and think they can deliver a different presidential candidate.

Drilling down on Harare

However, a finer-grained analysis of the geography of electoral support in Harare at the ward level helps to illuminate ZANU-PF’s interests and targets in Harare, including Mabvuku-Tafara, and Epworth, which ZANU-PF currently represents in parliament.

The 2018 election results for council elections indicate that the opposition retains strongholds in Budiriro (Ward 33 and 43), Glen Norah (Ward 27), Harare Central (Ward 2), Hatfield (Ward 23), Highfield East ( Ward 24 and 25), Highfield West (Ward 29), Kuwadzana (ward 44), Kuwadzana East (Ward 37), Warren Park (Ward 15), and Glen View South (Ward 32). The following six wards, while in mainly opposition hands, are seriously contested terrain:

- Harare South (Ward 1), in the 2023 election, has now been divided into three constituencies (Churu, Manyame, and Harare South). ZANU-PF won this constituency in 2018 and hoped to retain the three new ones.

- Mabvuku-Tafara (Ward 21), where gold dealer Scott Sakupwanya has been investing heavily in campaigning through infrastructure development.

- Mbare (Wards 3 and 4), which ZANU-PF won in 2013, may have legitimate hopes of retaining.

- Mt Pleasant (Ward 17, and 7), a reasonably elite suburb that in 2013 was a battleground won marginally by the MDC-T, and in 2013 produced a three-horse race between the MDCT, ZANU-PF, and now CCC candidate Fadzai Mahere who was an independent. The ZANU-PF and independent votes there were more than the MDC-T’s.

- Warren Park (Ward 5).

The above indicates opposition dominance and fierce political contest in some of Harare’s high-density suburbs. This is the case except for Mt Pleasant in the Battleground column and parts of Hatfield in the Opposition Stronghold Column. The rest of the list constitutes a veritable collection of some of Harare’s poorest and most densely populated parts. The geography of partisan alignment in Harare is open to a few suggestions. First, two heavily congested areas, Mabvuku-Tafara and Harare South, are on the city’s periphery, where they join Epworth to constitute the southern and south-eastern edges of the city. Harare South (Ward 1) was the largest Ward in the city, with over 76,425 eligible voters as of 2018, which is why it is now three constituencies and was constituted mainly of parts of what has traditionally been Harare Rural. Epworth has its own Local Board but is part of Harare Metropolitan Province. At the same time, Mabvuku and Tafara constitute the edge of Harare before getting into Mashonaland East Province at the border with Ruwa Town Council. Harare South also borders the dormitory town of Chitungwiza to the south.

The above suggests that ZANU-PF has decent election chances at the periphery, where the city borders dormitory towns and informal settlements. Party alignment has not been as oppositional in these places as the generalized analysis presents. This is partly a result of gerrymandering during delimitation processes, which led to the introduction of some peri-urban and rural areas as part of Harare. Resettlement schemes have also led to assembling settlers in certain areas with insecure tenure, whose presence on the land relies on ZANU-PF’s backing. The ZANU-PF-led central government has allowed these people to settle with little disturbance. However, it has also occasionally demolished some settlements to show the results of errancy in areas like Epworth and Harare South.

The presence of ruling party support against the general grain in the City of Harare is almost understandable, given informal settlements, as stated above. However, the data also shows some central Harare wards are seriously contested, including arguably the poorest and oldest suburb in Harare, Mbare. Wards 3 and 4 of Mbare have consistently turned Battlegrounds over the last two elections. Besides being battlegrounds, they have also swung between the ruling party, which won both wards in 2013, and the opposition, which reclaimed Ward 3 in 2018, with ZANU-PF winning Ward 4.

The battleground nature of the Wards in Mbare is also informed by informality regarding settlement and the economy. Mbare is central to informal trade in Harare, and economic opportunities, including access to trading stalls and transport hubs, are heavily politicized. There is clear politically mediated access to economic opportunities in Mbare and chances for rent-seeking by the council, party-aligned touts, and space barons.

Another confounding area is Mt Pleasant’s wards 7 and 17 from 2018, reported to have the most expensive land per square meter in Harare, because of “old money” and extensive economic, diplomatic, and educational activities in the constituency. Ward 17 has swung from ZANU-PF in 2013 to a marginal victory for the opposition in 2018. That the incumbent Harare Mayor Councillor Jacob Mafume was from this area also makes it a prime target for campaigning by ZANU-PF, although he has since switched constituencies. The reality is that the middle class and wealthy residents of Mount pleasant, in general, engage in limited political activity, with their domestic help (gardeners and maids in the main) being more involved in shaping the political destiny of the Ward, informs this confounding finding.

A similar pattern is discernible in the old Harare North, which houses some of the most affluent suburbs in Harare, like Borrowdale, Mandara, Chisipite, and Shawasha Hills. Ward 42 of Harare North was won by ZANU-PF in 2013 before being reclaimed by the opposition in 2018 based on similar political developments. In 2013, the Ward and the constituency, represented in Parliament by CCC Vice President and Former Finance Minister in the GNU, Tendai Biti, was specifically targeted for the extensive campaign by ZANU-PF in 2013 to remove the “troublesome” Minister from Parliament. In 2018, Vice President Retired General Dr Chiwenga made campaign stops in the Ward, where he, the president, and other ZANU-PF elites also reside. ZANU-PF’s support in Harare straddles several cleavages, which include political, military, and business elites and subordinate classes dominated by civil servants, housing cooperatives, informal settlers, and ordinary card-carrying members of the ruling party. The elite and powerful in this group are mainly residents in the Northern Suburbs – usually affluent low-density areas. However, while the opposition is dominant or fairly dominant across most of the city’s north and central zones, there are some contested wards and constituencies closer to the centre and the southern, peri-urban neighbourhoods of the city, where informal settlements often create clients for the ruling party.

Conclusion: Race to watch

The 2023 election is much more competitive than a casual look might suggest. At the provincial level, the battlegrounds which are likely to have stiff electoral competition are Manicaland, Matabeland South, Matabeleland North, Midlands and Mashonaland West. Harare and Bulawayo are likely to retain their opposition colours, while Mashonaland Central, Mashonaland East, and Chamisa’s home province Masvingo will likely stay ZANU-PF. The margins of victory across the battleground provinces are likely to determine the fate of the presidency. Chamisa’s task will be to cut down Mangagwa’s support in his strongholds and turn over some of the battleground provinces to stand a chance while also increasing his margins in Harare and Bulawayo. For Mnangagwa, the main play is a defensive one across the board with hopes of some gains in Harare and Bulawayo provinces. There are limited possibilities of a runaway victory either way, and the victor will depend a lot on who can turn out their supporters the most on 23 August 2023.

At the constituency level, 52 constituencies are likely to offer very competitive races. Thirty-four constituencies are solidly ZANU-PF, 19 solidly opposition, with the rest being marginal either way. Suppose the main parties can defend their strongholds and leaning constituencies, who gets what in parliament will be down to who gets the lion’s share of the 52 battleground constituencies. Ahead of the elections, ZANU-PF has 86 constituencies trending its way, while the CCC has 72. On this calculus, avoiding a two-thirds majority either way is possible depending on how the parties defend their strongholds and gain from the battlegrounds.