NEWS

December 7, 2021

IN BRIEF

By Zulfiqar Younus Developing public service capability, productivity and innovation is increasingly important to rebuild public trust in the government. To meet this challenge, it is essential to identify the skills, competencies, and leadership styles required of civil services for an innovation-ready public service. Civil servants in senior administrative positions are expected to work across organizational precincts and jurisdictions to design and implement innovative initiatives to address emergent policy challenges and improve the impact of public service delivery. They need to balance conflicting objectives, motivate, inspire and lead their workforce. Civil service leaders are also needed to act diligently to [...]

SHARE

By Zulfiqar Younus

Developing public service capability, productivity and innovation is increasingly important to rebuild public trust in the government. To meet this challenge, it is essential to identify the skills, competencies, and leadership styles required of civil services for an innovation-ready public service.

Civil servants in senior administrative positions are expected to work across organizational precincts and jurisdictions to design and implement innovative initiatives to address emergent policy challenges and improve the impact of public service delivery. They need to balance conflicting objectives, motivate, inspire and lead their workforce. Civil service leaders are also needed to act diligently to accommodate fast-moving political agendas and respond to unpredictable incidents and changes in the society in accordance with the needs and expectations of elected officials, citizens, and stakeholders in an environment of increasingly fast-paced and disruptive change, impelled by an increasingly digital society and economy. Rising to this challenge demands public service leaders with the skills, mindsets, and tools to continuously innovate in an increasingly digital government, economy, and society.

These leadership challenges are aggravated by the fact that public services are impeded by the policies and practices that were intended for a past context. In response, the government needs to prioritize reforms that emphasize institutionalizing responsive, agile, and innovative senior leadership to reform the civil services they lead.

While our civil servants are given old school and outdated governance tools, they are expected to solve problems quickly and turn in the results almost instantly in a technology-enabled context where feedback, both from citizens and those in power, is received in real-time. A big part of the problem is the larger system in which we have to operate. Pakistan’s rank in the Global Innovation Index is currently at all-time low of 107th out of 127 countries, meaning we are among the world’s 25 least innovative countries, despite being in the top five largest nations in the world. Our system- both for the public and private sectors- is currently not set up in a way that encourages or supports innovation. Education teaches linear thinking; incentives within our culture are to maintain the status quo; patriarchal and ageist systems prevent the emergence of ideas from the younger generation of bureaucrats and entrepreneurs; and large swaths of the population are excluded by law and practice- from decision-making.

In the face of these challenges, there is a need for the civil service now more than ever, to improve and innovate. But what does innovation in the public sector even look like in a place like Pakistan? How can we ensure that it happens? And where do we start?

First, while innovation provides a competitive advantage within the private sector, there are not the same incentives within the public sector- in fact, quite the opposite. Change can be difficult and there can be bureaucratic resistance to reforms. The key is finding reformers who understand that reform is needed for altruistic reasons; and building teams around them that realize in addition that innovation can improve outcomes. In February last year Gulf News printed a story with the caption “In the Pakistan Administrative Service, there is an officer who works to change”. It was about an aspiring civil servant of Islamabad who is the face of that change and has redefined the idea of work with his innovative approaches to engage with the general public and think beyond the boundaries of his institutional responsibilities. Put simply, public sector innovation needs to be about building support for new ideas that create public value.

Second, the challenge with the “traditional “approach to innovation is that civil servants in particular feel like they need to answer the problem at hand and quickly scale-up solutions to that problem- but more often than not, they cannot identify this problem. Governance is messy- but too often we continue to engage in social innovation and policymaking around it as if change happens in a straight line- because it is easier that way. Scholars have been arguing for years that we get caught in a process of path dependency when trying to innovate our way out of problems. We presume “rational innovation journeys” through which technological innovations somehow scale and diffuse at some point through mass government adoption. But often, we are actually dealing with the symptoms of problems, not their causes. The way to understand the real causes is to speak with citizens and find ways to continually channel their feedback into decision-making.

There are countless examples of innovation going wrong in the public sector because the goal is not actually to solve problems for citizens, it is to respond to a larger directive, please a superior or use a new technology as an end in itself. Innovation that is fashionable does not ensure substance or impact. As Oscar Wilde hinted, policy fashions are a form of shallowness so intolerable that we have to change them every six months.

Third, citizens are not adequately included in the process of innovation. Feedback and trust are central elements of any reform process- but these need to be built over time. If civil servants were to begin to rethink their role not as agents for delivery but as facilitators between citizens and the government, they may well be better able to solve problems. Towards that end, civil servants in Pakistan today need to be equipped with the tools- and more importantly the mindset- to engage citizens to create meaningful changes in society through innovation. Some civil servants have started using social media platforms to interact with citizens and receive direct feedback. Others are using technology to track the progress of their subordinates and report progress; still others are working on developing authorized and fully connected databases for better service delivery. The key is that the technology becomes a tool as part of a strategy towards a goal; not the end in itself.

Fourth, there are a set of ongoing discussions here about creating internal spaces for reflection and reform inside bureaucracies- as have been piloted elsewhere- such as the PLC Lab in Mexico City, or Portugal’s SIMPLEX. These spaces allow room to test new policy processes and implementation mechanisms. The question in Pakistan is where to position these bodies to ensure political buy-in and avoid the design flaw at the outset that positions these kinds of initiatives outside mainstream practice and therefore inevitably a side-show rather than a hub for change. Commitment from the top-down from the Prime Minister’s Office and key ministries is essential; and provincial level versions with the backing of our sub-national bodies would make sense, given the diversity and size of Pakistan.

Finally, another promising approach is to celebrate and award innovative approaches to management- as with Canada’s IPAC award, for example, which recognizes the top innovative individuals based on three criterion: implementation of effective organizational change, the transition of new ideas into practice, and harnessing new technology. We know in Pakistan that “naming and faming” civil servants works extremely well not only to motivate these individuals but at a deeper level to encourage others to push back against systemic inefficiencies. Pakistan would also benefit from introducing an innovation award for its public officials to encourage greater innovation in the public sector- perhaps focusing on the outset on critical issues identified by citizens.

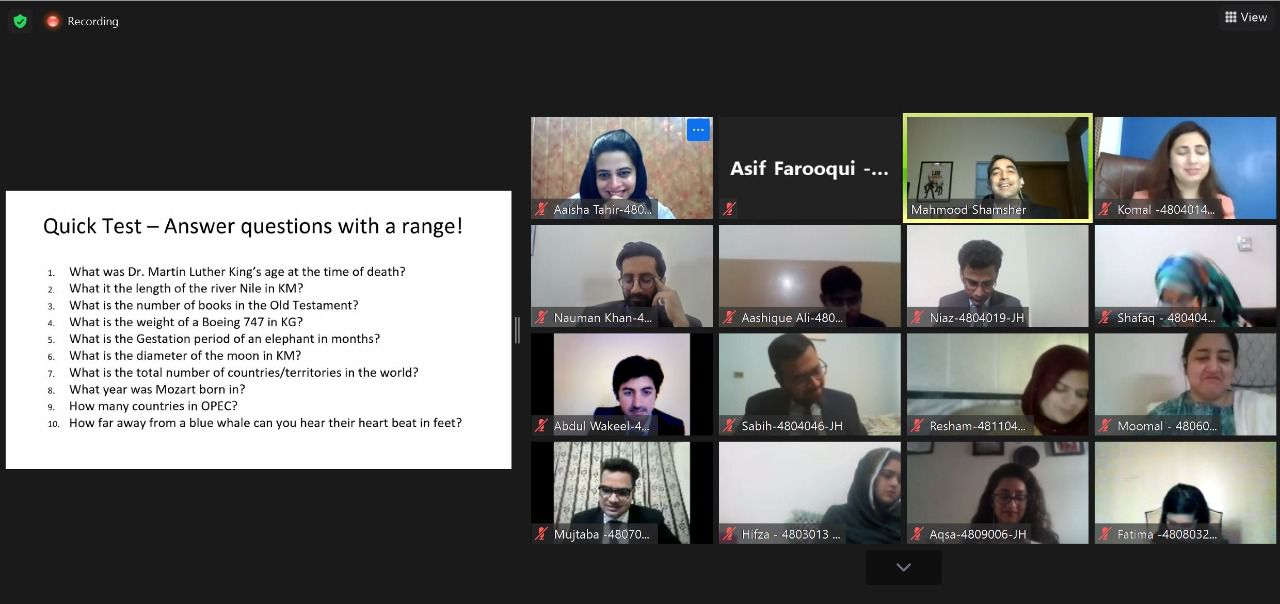

The Civil Services Academy in Lahore (our training school for civil servants) is constantly working to update its curriculum to ensure that these kinds of ideas can influence the next generations of civil servants. Over the past few years, the CSA has partnered with Accountability Lab Pakistan to run Accountable Leadership and Design Thinking workshops for trainee civil servants. These programs support the new recruits to develop a 360- degree perspective around self and social accountability, and prepare them for real life challenges by integrating feedback and adaptive governance processes into their work.

Finding innovative solutions to governance challenges in a difficult context such as Pakistan is never easy- but our government must be oriented in a way that allows the thinking around this process to take place; and incentivizes change. We can see from elsewhere how innovation is possible- and our goal should be an adaptive, flexible administration, full of people that are empowered to try new ideas, learn from the process of innovation and collectively co-create better outcomes with- and for- citizens.

Zulfiqar Younus is former Director of the civil services academy, Lahore.