NEWS

July 10, 2017

IN BRIEF

This post was originally published by the Nonprofit Chronicles. By Marc Gunther The global south is littered, literally, with the remains of failed international aid projects. So-called clean cookstoves had more appeal to western donors than to women in India, Africa or Latin America. Wells and taps that were intended to provide clean water have fallen into disrepair. One 2009 study estimated there are 50,000 broken rural water points across Africa that represents a failed investment of US $215-360 million. Oops. It’s easy to understand how this happens. If a nonprofit provides cookstoves or water taps or chickens or books, that’s what it will give poor [...]

SHARE

This post was originally published by the Nonprofit Chronicles.

By Marc Gunther

The global south is littered, literally, with the remains of failed international aid projects. So-called clean cookstoves had more appeal to western donors than to women in India, Africa or Latin America. Wells and taps that were intended to provide clean water have fallen into disrepair. One 2009 study estimated there are 50,000 broken rural water points across Africa that represents a failed investment of US $215-360 million. Oops.

It’s easy to understand how this happens. If a nonprofit provides cookstoves or water taps or chickens or books, that’s what it will give poor people, even if what they really want is malaria nets, a schoolhouse or cash.

As Jennifer Lentfer puts it: “One of the killer assumptions that has plagued the aid industry for years now is the idea that there’s a blank canvas upon which our interventions will make things better.”

Lentfer and Tanya Cothran are editors of a new book of essays called Smart Risks: How small grants are helping to solve some of the world’s biggest problems. Lentfer, who is director of communications at the nonprofit Thousand Currents (formerly IDEX), and Cothran, who is executive administrator of a foundation called Spirit in Action, believe that community groups in poor countries know better than experts in the west what they need.

Both are small organizations, so it’s no surprise that Lentfer and Cothran focus on small grants. Thousand Currents gave away just under $1 million in 2015, the last year for which a financial report is available on its website. Spirit in Action reported donations of just $34,000 on its 2015 Form 990.

Most of the international grant-makers who contribute to Smart Risks also embrace the small-is-beautiful mantra. More important than how much they give, though, is how they give. They support grassroots groups with flexible, unrestricted, long-term support.

In an essay called “The five essential qualities of grassroots grant-makers,” Jennifer Astone, executive director of the Swift Foundation, asks:

Why not rethink the model of pushing money and projects onto communities, and instead let local priorities determine the needs and drive the design and pace of the work?

Why not, indeed? But this bottom-up approach to global grant-making evidently remains unusual. A report on global humanitarian assistance released last week by Development Initiatives found that national and local responders directlyreceived just 2% of funding reported to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Financial Tracking Service in 2016. That said, much funding for grassroots groups flows through intermediaries like Thousand Currents, Spirit in Action, Global Giving, Accountability Lab, and the Urgent Action Fund. These groups are showcased in Smart Risks.

Smart Risks has stories of solutions generated by local people that could never have been imagined by western grant-makers. In an essay called “Small grants as seed funding for entrepreneurs,” Caroline J. Maillou, a consultant, describes how a global health nonprofit solicited ideas from faculty and students who were training for health careers. They learned that a small grant for mattresses and the renovation of a simple dormitory in Uganda was enough to persuade more students to work in a rural community.

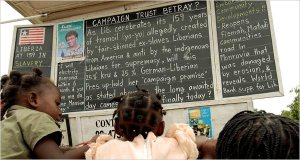

Blair Glencourse, the founder and executive director of Accountability Lab, writes about The Daily Talk, which delivers news headlines each day on a blackboard at a busy corner in Monrovia, Liberia. (See All the News That fits: Liberia’s Blackboard Headlines) Also in Monrovia, Accountability Lab funds Thomas Tweh, a community leader who “trains volunteer mediators to serve on community justice teams that resolve disputes by building trust and understanding among the parties.” In a single year, these community justice teams resolved almost 80 cases, reports Glencourse:

Blair Glencourse, the founder and executive director of Accountability Lab, writes about The Daily Talk, which delivers news headlines each day on a blackboard at a busy corner in Monrovia, Liberia. (See All the News That fits: Liberia’s Blackboard Headlines) Also in Monrovia, Accountability Lab funds Thomas Tweh, a community leader who “trains volunteer mediators to serve on community justice teams that resolve disputes by building trust and understanding among the parties.” In a single year, these community justice teams resolved almost 80 cases, reports Glencourse:

This saved the partners involved almost 500,000 Liberian dollars ($5,000) in fees (and bribes) and approximately 350 days of time that people would have been engaged in legal proceedings. All this for an investment of just $3,000.

Smart Risks also delivers practical advice for grant-makers and ideas for individual donors who want to support global development. At a Washington, D.C., book launch last week, Lentfer said: “Church ladies who have a donor circle were in the back of our minds. They don’t need to build an orphanage. There’s a lot of good work going on.”

But a question nagged at me while reading Smart Risks: Why small grants? These days, at least among the US’s best-endowed private foundations, aren’t “big bets” the new new thing?

Caitlin Stanton of the Urgent Action Fund thoughtfully tackles that question in an essay called “When small is too small: Recognizing opportunities to scale smart risks,” She reports that during a decade when she worked at the Global Fund for Women, the group awarded more than $80m in small grants, the vast majority for $20,000 or less.

This seems, at the very least, inefficient, requiring a high overhead ratio to pay for the staff, offices and travel budgets needed to push that money out the door. “It can cost just as much to make a $50,000 grant as it can to make a $5,000 grant,” Lentfer acknowledged last week. But, she added, the costs of making an initial grant and the time required to build trust with community groups are repaid over many years because of the long-term commitments that groups like Thousand Currents makes to its local partners.

Even as Stanton argues that foundations should seize opportunities that arise to help their partners grow, she writes that “small grants have played a powerful role in seeding human-rights and social-justice movements at the grassroots.”

I’m not persuaded. Were the civil rights, feminist or LGBT movements seeded by small grants? What about democracy or human rights movements overseas? Can small grants really make a big difference? I’d like to see more evidence.

That said, putting money and power into the hands of poor people and communities makes more sense than the old-school, top-down approaches. The bottom-up style of grant-making has also influenced others in philanthropy to become better listeners, so that today’s clean-water or cookstove projects are more likely to succeed than past efforts. Supporting grass-roots groups also strikes me as more likely to be effective than starting yet another NGO or “social enterprise.” Funders like the Novo Foundation, Open Society Foundation, Humanity United and the Libra Foundation deserve credit for their willingness to support intermediaries like Thousand Currents and Accountability Lab. Small grants may deliver only small gains, but to those who they touch directly, they’re a big deal.