NEWS

December 15, 2016

IN BRIEF

By: Marc Gunther. This article was originally published on Nonprofits Chronicles. In the US, Integrity Idol might not qualify as must-see TV. The TV-and-radio show showcases five government officials, nominated by their fellow citizens, who are known for their honesty. People vote for their favorite civil servant via text messages or online, and the winner is crowned in a ceremony in the national capital. In Nepal, though, Integrity Idol is a hit. Last year, reached an estimated 3 million viewers (10 percent of the population), generated 10,000 votes and celebrated the work of a education reformer named Gyan Mani Nepal, who cleaned house [...]

SHARE

By: Marc Gunther. This article was originally published on Nonprofits Chronicles.

In the US, Integrity Idol might not qualify as must-see TV. The TV-and-radio show showcases five government officials, nominated by their fellow citizens, who are known for their honesty. People vote for their favorite civil servant via text messages or online, and the winner is crowned in a ceremony in the national capital.

In the US, Integrity Idol might not qualify as must-see TV. The TV-and-radio show showcases five government officials, nominated by their fellow citizens, who are known for their honesty. People vote for their favorite civil servant via text messages or online, and the winner is crowned in a ceremony in the national capital.

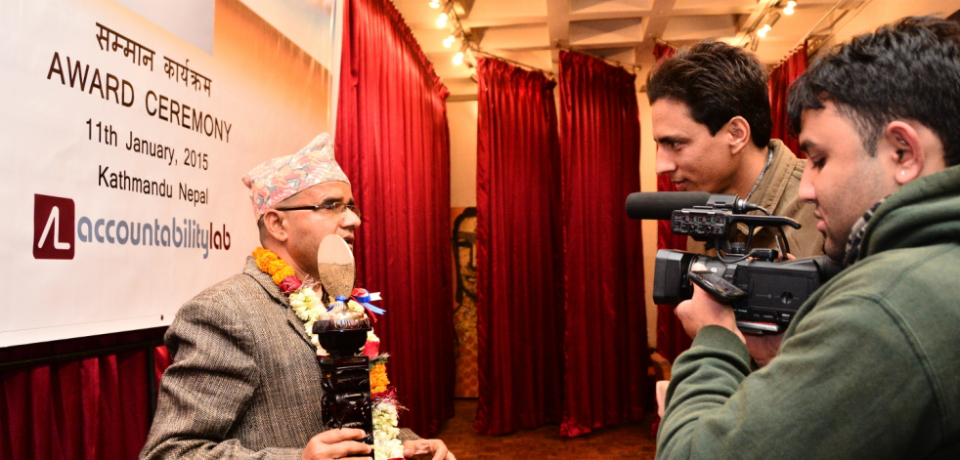

In Nepal, though, Integrity Idol is a hit. Last year, reached an estimated 3 million viewers (10 percent of the population), generated 10,000 votes and celebrated the work of a education reformer named Gyan Mani Nepal, who cleaned house in a rural school district. It’s back again now, with new episodes rolling out.

More important, according to Blair Glencorse of Accountability Lab:

The program created a national discussion — online, in tea shops, and among families — about what it means to be a public official in Nepal and what it takes to demonstrate integrity within a corrupt and deeply politicized system.

Glencorse is the founder and executive director of Accountability Lab, a nonprofit that helps young people in the global south to promote accountability and transparency. Launched in 2012 and based on Washington, D.C., Accountability Lab trains and supports local people in four countries –Nepal, Pakistan, Liberia and Mali — to use media, culture, education and technology to make government work better for them and reduce corruption.

“We’re building a new generation of young people who value accountability and integrity and can push for the kind of change they want to see,” Glencorse says.

This makes sense to me. While many well-intentioned nonprofits provide the global poor with health care, education or job training (albeit with disappointing results), Accountability Lab aims to get their governments to work on their behalf.

“Unless we can get the relationship between people in power and citizens right, it will hard to do anything else,” Glencorse says.

Or, as the Nobel prize winning economist Angus Deaton argued in The Great Escape: “Poverty an underdevelopment are primarily consequences of poor institutions.”

I’ve run into Blair Glencorse occasionally at events in Washington, and we had a chance to spend some relaxed time together last fall at Opportunity Collaboration, a conference about global poverty in Cancun, Mexico. A Brit, Glencorse, 37, worked at the World Bank and at a think tank called the Institute for State Effectiveness before starting Accountability Lab with a grant from Mistral Stiftung, a small Swiss family foundation. It’s a small organization that expects to bring in about $880k in revenue this year, most of that from foundations, including Open Society Foundations and Humanity United.

about global poverty in Cancun, Mexico. A Brit, Glencorse, 37, worked at the World Bank and at a think tank called the Institute for State Effectiveness before starting Accountability Lab with a grant from Mistral Stiftung, a small Swiss family foundation. It’s a small organization that expects to bring in about $880k in revenue this year, most of that from foundations, including Open Society Foundations and Humanity United.

Accountability Lab is itself a model of transparency. It publishes an up-to-date open budget which allows anyone to drill down in a detailed way to understand its finances, and it posts impact and learning reports to Google Drive where anyone can see them. The organization now has three full-time staff in the US and another 22 in the countries where it operates.

Glencorse got Accountability Lab started in Liberia, where he’d worked for the World Bank and knew some young activists. The NGO made a small investment to start a film school, whose students who have gone on to make short documentaries about trash collection, clean drinking water and sexual harassment. During the Ebola crisis, film school grads made local-language films, advising people on how to stay safe.

Accountability Lab has also sponsored a feisty Liberian newspaper called The Bush Chicken which, along with lifestyle and sports coverage, reports on the performance of government institutions. A story this week reported that a government-run facility that houses and educates orphans and vulnerable girls lacked sufficient food and a reliable supply of clean water. Another story called for the speedy trial of the national leader of a student union who has been accused of rape.

This is atypical of the Liberian press, Glencorse told me. “Standards are awful,” he said.“Journalists are routinely bribed to put out articles.”

While Accountability Lab’s work differs from place to place, certain programs have traveled well. Each country has its own Integrity Idol (highlights in the video below), which is designed to “name and fame” do-gooders instead shaming those who are corrupt.

In Liberia, Nepal and Pakistan, the group has created what’s called an Accountability Incubator, a gathering place where young people are selected (and paid a modest stipend) to join a two-year program about accountability, integrity and transparency, while getting nuts-and-bolts advice about creating media or building organizations. Mali, the newest country for Accountability Lab, will soon get an incubator as well.

Measuring success is a challenge for the organization, Glencorse said. Accountability Lab published annual impact and learning reports that are better than most. Its most recent report includes results of a survey of government officials and people who participated in its programs, asking them if Accountability Lab is providing them with the right kind of support, and how it could do better.

The challenge for Accountability Lab will be to decide how and where to scale, assuming it can gather the resources needed to grow. (Donald Trump’s election won’t help; the group gets some support from U.S. AID.) Each expansion so far has been overseen by Glencorse, who spends about 80 percent of his time traveling. That’s not a scalable or sustainable model. Perhaps the organization can develop a toolkit, along with training, to help local groups devise programs on their own, provided they can raise the money to do so.

One thing’s for sure: Whether we’re talking about national or local governments in the global south, multilateral donors, global aid organizations or NGOs, the demand for accountability vastly exceeds the supply, and will do so for a long time to come.